Designing Argument

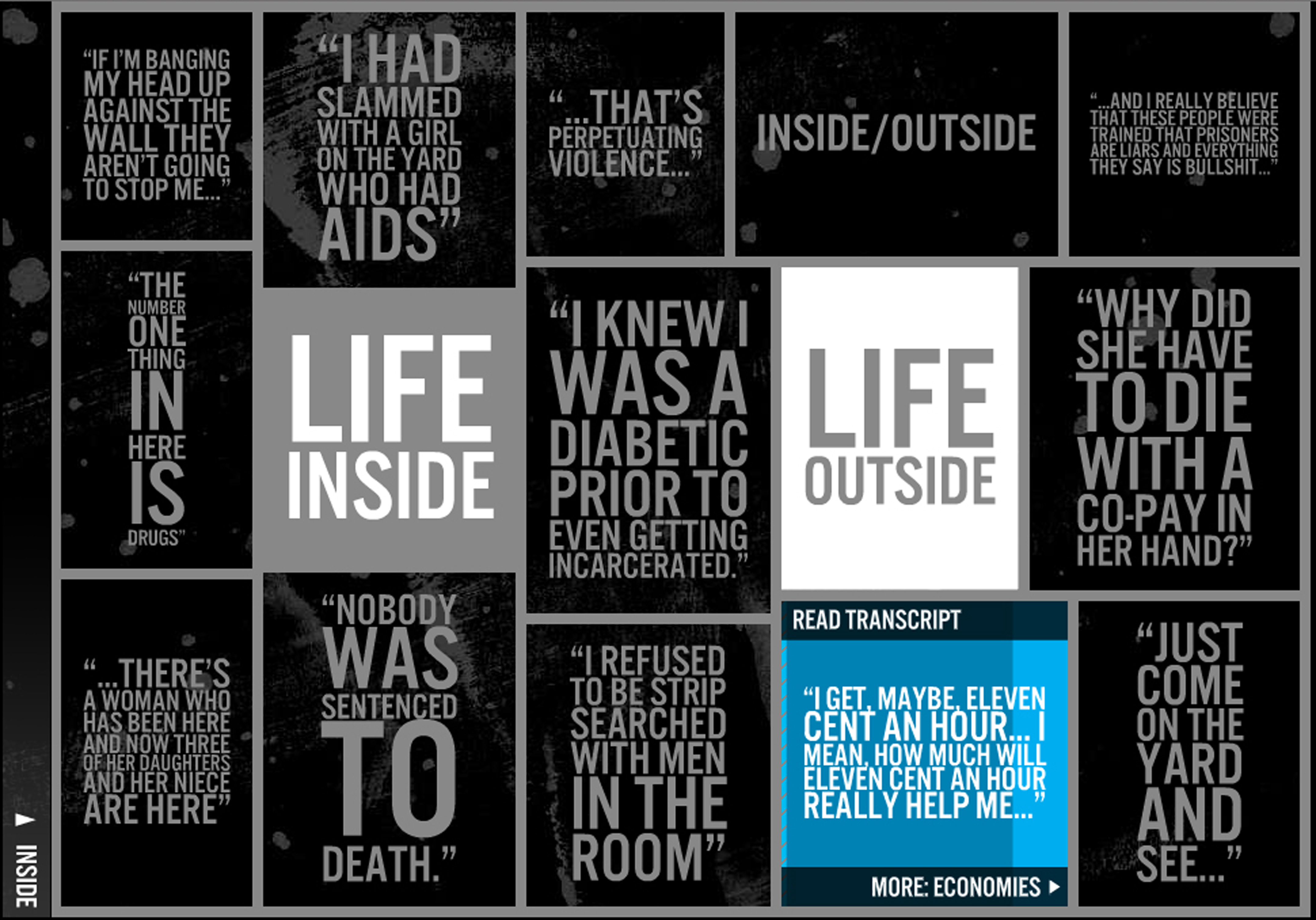

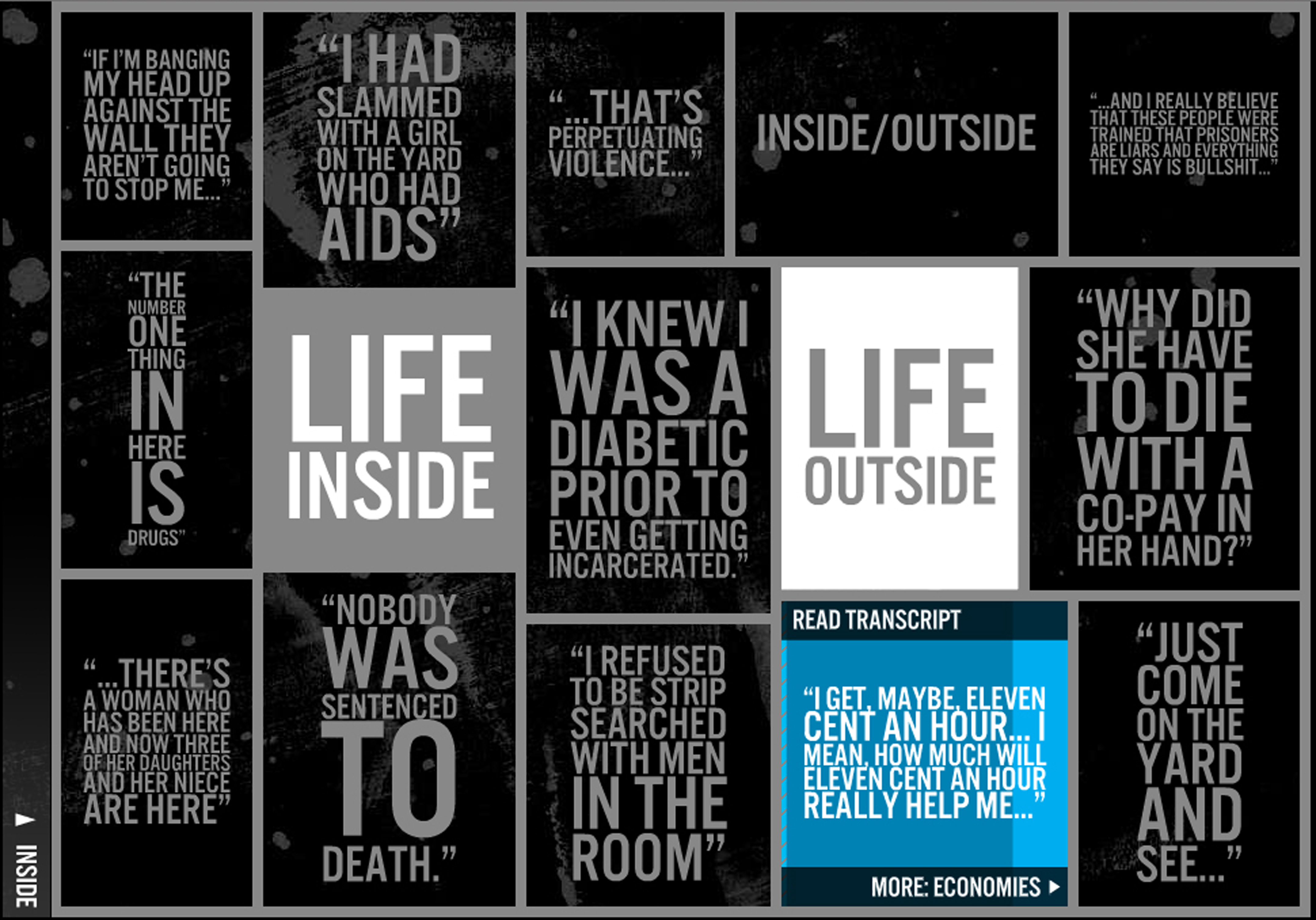

In Public Secrets and Blood Sugar interface and information design constitute a form of “argument.” While they are companion pieces that are very closely related in terms of content, participant-group, socio-political argument and visual identity, their underlying information architectures and resulting interaction designs reflect two, significantly different types of interview content.

In contrast to the array-like structure of Public Secrets, which allows the participants to speak collectively on topics that arose repeatedly in all of our conversations, the interviews in Blood Sugar are kept intact and whole. This significant difference between the two projects in both interface and information design is due to qualitative differences in the nature of the interviews themselves. The women who offered their testimony in Public Secrets were, for the most part, highly politicized. They consciously welcomed the opportunity to join their fellow prisoners in speaking to their issues in a collective voice. By entering the prison as a legal advocate, rather than a media-maker, I was able to interview most of the participants on multiple occasions and in a confidential setting. Over time I gathered considerable material, both personal histories and political opinions, that crossed a wide range of topics in which all the women shared a concern.

In contrast to the array-like structure of Public Secrets, which allows the participants to speak collectively on topics that arose repeatedly in all of our conversations, the interviews in Blood Sugar are kept intact and whole. This significant difference between the two projects in both interface and information design is due to qualitative differences in the nature of the interviews themselves. The women who offered their testimony in Public Secrets were, for the most part, highly politicized. They consciously welcomed the opportunity to join their fellow prisoners in speaking to their issues in a collective voice. By entering the prison as a legal advocate, rather than a media-maker, I was able to interview most of the participants on multiple occasions and in a confidential setting. Over time I gathered considerable material, both personal histories and political opinions, that crossed a wide range of topics in which all the women shared a concern.

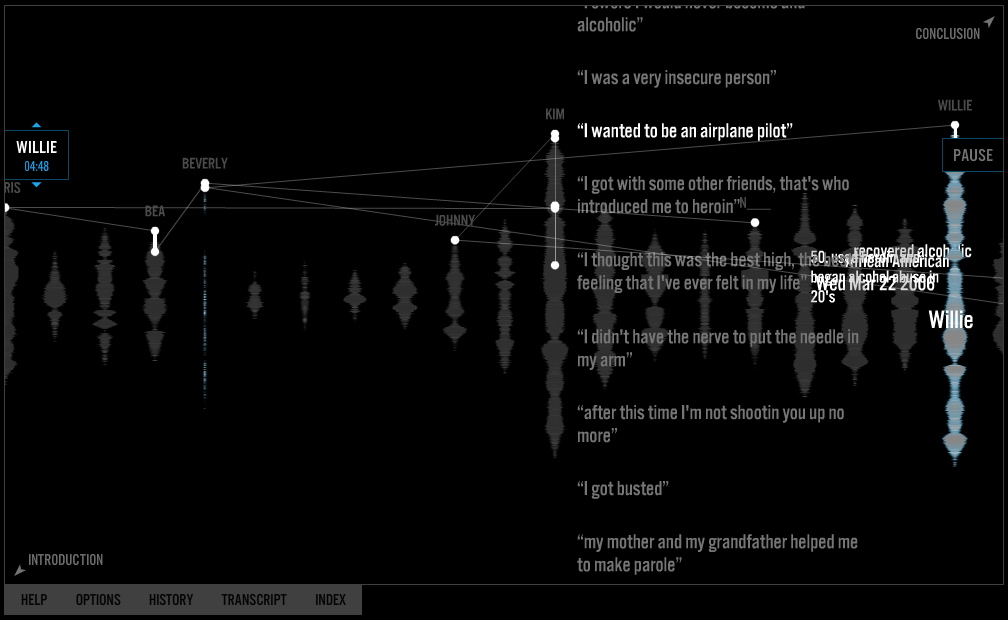

In contrast, I interviewed most of the addicts whose voices are heard in Blood Sugar only once. The setting where the interviews were held, during group therapy and education sessions at a harm-reduction-based social service facility, influenced the nature of our conversations. None of the addicts I met at the exchange presented the identity of the “righteous dope fiend,” which may well be the identity they present on the street. On the contrary, each act of self-narration began with a kind of confession of weakness or disease. The messy details of each life history would then unfold according to the syntax and grammar of the disease-and-recovery discourse that is learned in the type of quasi-therapeutic setting where we met. For the most part, my interlocutors did not frame their accounts in terms of social critique or analysis. Their focus was more on self-reflection than social criticism.

For this reason I decided that the Blood Sugar interviews should be available in their entirety as continuous narratives and that the interface should present each interlocutor as both an individual subject and body represented abstractly through the image of a wave-form or what I thought of as an "audio-body".

In contrast to the array-like structure of Public Secrets, which allows the participants to speak collectively on topics that arose repeatedly in all of our conversations, the interviews in Blood Sugar are kept intact and whole. This significant difference between the two projects in both interface and information design is due to qualitative differences in the nature of the interviews themselves. The women who offered their testimony in Public Secrets were, for the most part, highly politicized. They consciously welcomed the opportunity to join their fellow prisoners in speaking to their issues in a collective voice. By entering the prison as a legal advocate, rather than a media-maker, I was able to interview most of the participants on multiple occasions and in a confidential setting. Over time I gathered considerable material, both personal histories and political opinions, that crossed a wide range of topics in which all the women shared a concern.

In contrast to the array-like structure of Public Secrets, which allows the participants to speak collectively on topics that arose repeatedly in all of our conversations, the interviews in Blood Sugar are kept intact and whole. This significant difference between the two projects in both interface and information design is due to qualitative differences in the nature of the interviews themselves. The women who offered their testimony in Public Secrets were, for the most part, highly politicized. They consciously welcomed the opportunity to join their fellow prisoners in speaking to their issues in a collective voice. By entering the prison as a legal advocate, rather than a media-maker, I was able to interview most of the participants on multiple occasions and in a confidential setting. Over time I gathered considerable material, both personal histories and political opinions, that crossed a wide range of topics in which all the women shared a concern. In contrast, I interviewed most of the addicts whose voices are heard in Blood Sugar only once. The setting where the interviews were held, during group therapy and education sessions at a harm-reduction-based social service facility, influenced the nature of our conversations. None of the addicts I met at the exchange presented the identity of the “righteous dope fiend,” which may well be the identity they present on the street. On the contrary, each act of self-narration began with a kind of confession of weakness or disease. The messy details of each life history would then unfold according to the syntax and grammar of the disease-and-recovery discourse that is learned in the type of quasi-therapeutic setting where we met. For the most part, my interlocutors did not frame their accounts in terms of social critique or analysis. Their focus was more on self-reflection than social criticism.

For this reason I decided that the Blood Sugar interviews should be available in their entirety as continuous narratives and that the interface should present each interlocutor as both an individual subject and body represented abstractly through the image of a wave-form or what I thought of as an "audio-body".

| Previous page on path | Inquiry | Argument, page 1 of 2 | Next page on path |

Discussion of "Designing Argument"

Add your voice to this discussion.

Checking your signed in status ...